Kikopa Games’ Minkomora places you in a strange world of bright colors and abstract shapes forming a myriad of creatures, characters, and environments. You start in the small, modest home of your character and head out to explore. Outside your house is a message reading: ”Don’t be afraid of dying or missing out” and a hint to press Enter to find your way back home. This world is full of red triangular things surrounded by a squiggly red aura that affects the music while turning your character’s face red and distorting the screen when you stand near it. The world hosts plenty of other figures, some that seem to represent people, others that seem to represent plants, and others that represent…um, I don’t know--blobby things. Or at least I didn’t know what those blobby things were until I read the game’s digital manual.

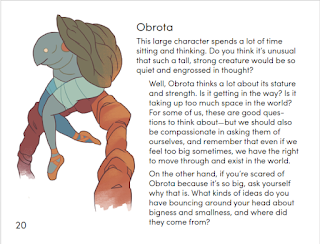

Minkomora can be played in-browser and comes with a pdf download of a manual with instructions of the game’s controls alongside beautifully drawn art of the characters and a detailed map of the world as well as descriptions for each of the places you can visit and the creatures you can meet. The manual communicates the games values, which are directly in line with merritt kopas’s Soft Chambers, a design philosophy emphasizing warm introspection, emotion, and explorations of caring relationships. The manual gives life, detail, and meaning to Minkomora’s world, depicting the obscure, blobby characters of the game with clear shapes and physical attributes not seen in the game. You can identify immediately which characters correspond to what in-game representation, but the manual’s art fills in the gaps of your imagination. For example, we recognize the player character in the manual from the moon-shaped mark on its face that also appears in the game. But during play, we see the character wearing an ambiguous purple outfit, while the manual depicts the character in a sweatshirt-skirt combo.

I learn through the manual that the “red triangular things” are plants called Kitagona that emit heat that may feel pleasant to some and overbearing to others. I learn that each of the characters represents a intrapersonal or interpersonal temperament or behavior, and the manual suggests how these traits might make one feel and asks what I think and how I relate to them. The manual tells me I deserve care, reminds me that some creatures need time to develop trust in others, and asks me how extreme dedication to a task can be dangerous.

I’m too young to have any meaningful nostalgia for videogame manuals. The only manuals that I have a memory of looking at are Sonic Heroes’--you know, the one that describes Eggman as a feminist--and Jak and Daxter’s fold-out map and guide that I ripped because seven-year-old boys have no patience with folding. But Minkomora’s manual invokes such a nostalgia, as Leigh Alexander and Mike Joffe note. The game, however, doesn’t incorporate nostalgia to indulge in past gaming memories, as Joffe also mentions, but rather to subvert our expectations by providing a guide for a game space that is safe and welcoming rather than one that is hostile and demands to be mastered or conquered.

Minkomora is much like the original Legend of Zelda. In both games, you play as a silent protagonist thrust into a strange world with distinct areas that you’re free to explore. You encounter indecipherably designed creatures with weird names and have to figure out how your character relates to them. Of course this is where the two games branch off. In the Legend of Zelda your relationship to the strange creatures is one of aggression, in which the crude sprites attack you and throw shit at you on sight. The solution to their assault is to fight back, you find, since pressing A causes you to thrust out a sword. Your relationship to the game world, then, is based on mastery of the combat so that you can navigate the environments safely, discover new areas, and face more challenging foes. Minkomora, in implicitly acknowledging its similarities to Zelda, lets you know up front (even without the manual) that in this world you don’t need to employ the violence you’ve been habituated to use in games. “Don’t be afraid of dying or missing out.” You cannot be killed in this world, and you can always come back. You can’t thrust out a sword or throw bombs or shoot arrows; you can only walk and sit. Minkomora only asks that you take in the sights and sounds of a place and that you think about how that place makes you feel.

Unfortunately, on my first run, I didn’t know how to feel about Minkomora.

The game’s itch.io page reads: “You can read the manual first, keep it with you while you play, or play first and compare your interpretations with those in it later.” I tend to want to dive into a text with as little influence from what’s outside the text as possible, aiming for a “pure” initial response that can be challenged through reading reviews, criticism, and other examples of what I recently learned is called paratext after engaging with a piece of media. For example, after finishing a game, I often type its title into the search bar of Critical Distance to look for pieces that either articulate and clarify abstract feelings I have about the game or provide a perspective I haven’t even considered. Though I couldn’t and didn’t want to avoid the paratext of Minkomora’s web page, I decided to avoid the manual at first because it involves direct interpretations of the game world and the objects represented in it.

The first time I took my character out of its home was a confusing experience that left me anxious and disappointed in myself. While roaming around the world of Minkomora was somewhat pleasant with its bright colors and cute music, I was unable to meaningfully engage with the game because I was too wrapped up in finding a meaning to the objects in the space that I could test against the manual’s interpretations. I wasn’t emotionally connecting with the space because I was looking for an immediacy to the answers about why the characters exist and the reasons for their designs, and I didn’t want to rely on the authors to give me those answers. I wanted to come up with them on my own and have my own thoughts, at least before reading the manual. But the focus on this self-indulgent, shallow end goal of “figuring out” Minkomora in order to feel smart damaged my experience with the game. In my impatience to understand the game’s meaning, I failed to heed to the latter part of the game’s message, “Don’t be afraid of...missing out.”

In both my schooling and in the criticism I read, I am told patience and visiting works multiple times are very important in engaging with art and in meaning-making, and while I’ve definitely gotten better at working slowly towards understandings of works, my experience with Minkomora shows I still have a long way to go. I still sometimes feel an urgency to know what a text is saying and doing without taking the time to put the work in. Part of this impatience is certainly caused by critical inexperience and immaturity, but I think another part is pressure in critical spheres to be the person who can consistently say the Smart, Interesting, and Correct things about art--a pressure that you must always be on the ball and have the answers and wisdom ready to be imparted onto others, especially readers. This pressure can motivate me to go for the A in class and try to get more pageviews for this blog, but I think it also prevents me from not only enjoying art but also from developing a healthy pace to think through difficult or more obscure work and from thinking about how a work makes me feel.

I’d also like to tackle another reason why I didn’t read the manual before playing: the idea that the author’s intent should not matter to the player, who can and should form the meaning of the text on her own. While I still believe that an audience member’s interpretation that diverges from the author’s intent is 100% valid, to dismiss the author’s words on her own work entirely seems just as arrogant as the author irritated at her audience for not “getting it.” Shutting out conversations between authors and audiences only seems to limit our understandings of what we create and what we engage with. My fear was that Minkomora’s manual would try to dictate the game’s meaning to me and spoil whatever my personal experience would bring to the game, but the manual’s writing couldn’t be any less didactic. The manual constantly asks how you feel about the game’s characters and its spaces and wonders contemplatively about them rather than mandates concrete meanings. While I’m sitting here fretting about what these horseshoe-looking shapes are, Minkomora’s manual wants to foster a friendly, relaxed discourse about a world surviving on care.

For me, reading Minkomora’s manual turned the game world from a disorienting space into one I actively want to inhabit and explore. I’ve returned to the game several times after having read the manual, and those experiences have been much more enjoyable than the first time I played the game. I like hanging out with Kotnakon, a spider creature who carries me around the map out of its love for helping others but needs to rest after working too hard for others, reminding me of my plans to focus more on myself next semester. I like swimming alongside Nurek in the lake, though I never manage to lose myself so completely in my strokes as it does. The game’s manual gives me a way to relate to its world in a beautiful way that I probably wouldn’t have found even if I did have the patience to thoughtfully engage with Minkomora’s imagery on my own. The manual shapes my view of the game’s world as a friendly and mysterious place while at the same time letting me come to my own conclusions about how my character relates to the others and the areas outside its home. The manual is cute, charming, and opens up Minkomora’s world, and the game is certainly better for it. Next time I play an artgame like Minkomora, I just need to swallow my pride, stop worrying so much about my interpretive abilities, and stop being afraid of missing out. I'm never going to have all the answers, and I'm probably not even supposed to.